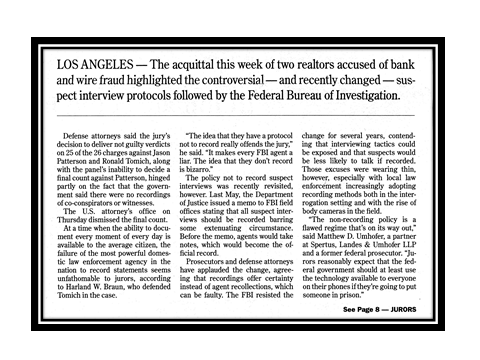

Los Angeles – The acquittal this week of two realtors accused of bank and wire fraud highlighted the controversial – and recently changed – suspect interview protocols followed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Defense attorneys said the jury’s decision to deliver not guilty verdicts on 25 of the 26 charges against Jason Patterson and Ronald Tomich, along with the panel’s inability to decide a final count against Patterson, hinged partly on the fact that the government said there were no recordings of co-conspirators or witnesses.

The U.S. attorney’s office on Thursday dismissed the final count.

At a time when the ability to document every moment of every day is available to the average citizen, the failure of the most powerful domestic law enforcement agency in the nation to record statements seems unfathomable to jurors, according to Harland W. Braun, who defended Tomich in the case.

“The idea that they have a protocol not to record really offends the jury,” he said. “It makes every FBI agent a liar. The idea that they don’t record is bizzaro.”

The policy not to record suspect interviews was recently revisited, however. Last May, the Department of Justice issued a memo to FBI field offices stating that all suspect interviews should be recorded barring some extenuating circumstance. Before the memo, agents would take notes, which would become the official record.

Prosecutors and defense attorneys have applauded the change, agreeing that recordings offer certainty instead of agent recollections, which can be faulty. The FBI resisted the change for several years, contending that interviewing tactics could be exposed and that suspects would be less likely to talk if recorded. Those excuses were wearing thin, however, especially with local law enforcement increasingly adopting recording methods both in the interrogation setting and with the rise of body cameras in the field.

“The non-recording policy is a flawed regime that’s on its way out,” said Matthew D. Umhofer, a partner at Speritus, Landes & Umhofoer, LLP and a former federal prosecutor. “Jurors reasonably expect that the federal government should at least use the technology available to everyone on their phones if they’re going to put someone in prison.”

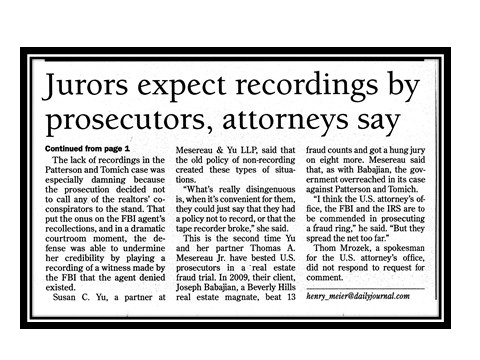

The lack of recordings in the Patterson and Tomich case was especially damning because the prosecution decided not to call any of the realtors’ co-conspirators to the stand. That put the onus on the FBI agent’s recollections, and in a dramatic courtroom moment, the defense was able to undermine her credibility by playing a recording of a witness made by the FBI that the agent denied existed.

Susan C. Yu, a partner at Mesereau & Yu LLP, said that the old policy of non-recording created these types of situations.

“What’s really disingenuous is, when it’s convenient for them, they could just say that they had a policy not to record, or that the tape recorder broke,” she said.

This is the second time Yu and her partner Thomas A. Mesereau Jr. have bested U.S. prosecutors in a real estate fraud trial. In 2009, their client, Joseph Babajian, a Beverly Hills real estate magnate, beat 13 fraud counts and got a hung jury on eight more. Mesereau said that, as with Babajian, the government overreacted in its case against Patterson and Tomich.

“I think the U.S. attorney’s office, the FBI and the IRS are to be commended in prosecuting a fraud ring,” he said. “But they spread the net too far.”

Thom Morzek, a spokesman for the U.S. attorney’s office, did not respond to a request for comment.